|

3.3.8 Bicycles for

small children

In 1986, Raleigh launched an innovative range of children’s

cycles with applied black plastic mouldings and electronic sound

generators. These bikes were developed using ideas that had been

piloted in the none too successful Vektar, in collaboration with

a small specialist electronics company in Spondon, Derbyshire.

Street Wolf, a 16" wheel machine aimed at 6-7 year-olds was

the most popular model, the others being Wild Cat, a 20" wheel

bike for 7-9 year-olds, and Wolf Cub, a junior version with stabilisers.

The latter set a new record for the most expensive bike ever sold

with stabilisers, retailing at about £70 (= about £120

today).

3.4

TI decides to sell

Despite all these marketing initiatives, particularly the initial

success of the Burner BMX range, things were not going too well

for Raleigh’s hub gear division. In 1982, Sturmey-Archer made

400 workers redundant. Burners were not Grifters, and did not have

hub gears: and although S-A introduced a specially strengthened

BMX axle, nobody wanted to put three-speeds into a BMX. S-A ceased

single-speed coaster brake production in 1982 and two years later

Dynohubs were dropped, 46 years after their introduction. Furthermore,

Britain’s long love affair with hub gears was waning. Derailleurs

were getting better, cheaper and more fashionable. Even Raleigh’s

women’s range made extensive use of derailleurs. But Sturmey-Archer

was not encouraged to develop them and, although S-A had prototyped

a seven-speed hub in 1973, TI was not prepared to invest in it.

(Not until the mid 1990s, after Sachs and Shimano had introduced

7-speed hubs, did S-A market one.)

By 1985, Raleigh itself was suffering badly, as BMX rapidly died.

Being essentially a bicycle designed for a seven-year-old but ridden

by 7-17 year-olds, there was no moving up to bigger machines as

riders grew. Everybody who wanted a Raleigh BMX bike bought it in

the first two years. Thereafter Raleigh’s UK sales plummeted.

By 1986, sales were 38% down on the 1983 peak. Moreover, initial

sales of the Maverick range were disappointing.

This dip in sales was matched by the industry as a whole, but Tube

Investments now lost patience with Raleigh. TI decided to sell the

company and, on 1st April 1987, it was bought by Derby International.

TI’s 27-year ownership of Raleigh, under successive MD’s

Leslie Roberts, Tom Barnsley, Ian Phillips, Rowley Jarvis and Bob

Ing, had seen market share drop from 75% to 36%. Under TI, Raleigh

was smothered: a relatively small division, unable to make important

decisions without reference to higher authority. There was a feeling

within Raleigh that its bosses were not really in charge. TI seemed

more interested in filling in five-year plans, rather than making

decisions. It was a huge conglomerate including not only industrial

tubing but consumer products such as Creda cookers, Russell Hobbs

kettles and Tower saucepans. TI did not see bicycles as being interesting

or particularly profitable. They retained ownership of Reynolds

tubing for a further decade, however.

3.5

Derby International

Derby was a private company, the name of which derived not from

the rival cathedral city 20 miles west of Nottingham but from the

American term for a bowler hat, as in the sense ‘top drawer’.

Its founder was Edward Gottesman, an Anglo-American tax lawyer,

domiciled in London for many years. It is somewhat ironic that,

a century after a lawyer founded Raleigh, another lawyer should

head the company purchasing it.

Gottesman, like Frank Bowden, was both entrepreneurial and interested

in bicycles. He had heard that TI was keen to dispose of Raleigh

and appreciated the value of the Raleigh brand, especially in America.

Therefore, he got together with some associates, put in his own

money and some from his colleagues, obtained the support of financial

institutions and formed Derby. Being a tax lawyer, he registered

the company in Luxembourg.

The banks required a chief executive officer with a proven record

of accomplishment. Hence, Alan Finden-Crofts, formerly with Dunlop,

was recruited. It is reported that, at his first meeting with Raleigh

dealers, he said that he had sunk everything he personally owned

into Raleigh. He wanted to make it clear that Raleigh was now a

small company whose CEO had financial commitment.

When Derby took over, a whole layer of Raleigh management was removed

at a stroke. For the doers who remained, it was a liberating experience.

Finden-Crofts told them that all he wanted to do was apply a slight

touch on the rudder. He was a strategist and did not wish to be

involved in the day-to-day activities. He said he believed in choosing

the right people, then letting them get on with it. Many staff found

this empowerment liberating.

What followed was an exciting but difficult time. For example, Raleigh’s

procurement manager suddenly found he could not buy materials on

credit, as Raleigh was a new company. Moreover, having been a user

of TI’s corporate information technology, Raleigh suddenly

lacked a computer system. A lot of foundation work was therefore

necessary, but most staff responded positively.

Derby initially acquired not only the Nottingham operation including

Sturmey-Archer but also Raleigh’s operations in the Netherlands

(including Gazelle), South Africa, Canada, Australia and the Irish

Republic. Subsequently they bought other companies, including the

German Kalkhoff company, now the main Raleigh outlet in Germany.

(For the situation regarding use in the USA of the Raleigh name

by Huffy, see Steve Neago's note. )

When Derby took over, Raleigh’s marketing director and deputy

left. Yvonne Rix was made product planning and marketing manager

and in 1988 was appointed marketing director, with a seat on the

Raleigh board.

For the role of managing director, Derby first brought back Sandy

Roberts, son of Leslie Roberts, from Raleigh International. Roberts

retired in 1990 and his successors were first Howard Knight, then

for a brief period, Mark Todd. In January 2000, Phillip Darnton

assumed the role. He was formerly MD of Unilever’s factories

in South America and marketing director on the board of Reckitt

& Coleman.

3.6

Significant models in the Derby period (1987-99)

3.6.1 The mountain bike boom

Alan Finden-Crofts believed that timing was everything and no sooner

had Derby acquired Raleigh than mountain biking in the UK finally

took off. Raleigh’s UK sales increased for the next four years

running and by 1990 were 31% on 1986. Eventually, more than 3m Raleigh

MTBs were sold. The move to profitability surprised many and confounded

the widely held view that Derby was only interested in asset stripping.

Initially dubbed ‘Dad’s BMX’, mountain bikes had

a much wider age profile than their smaller cousins: not 7 to 17

but more like 9 to 90. Eventually MTBs became the replacement conventional

bicycle, the equivalent in the UK of the now virtually extinct sports

light roadster. Nonetheless, the mountain bikes offered by Raleigh

still had a product life cycle. After four very good years, most

people who wanted a first generation Raleigh mountain bike, had

bought one. Consequently, in 1991, Raleigh’s total UK sales

dropped by 16%, a level at which they were to remain for five years.

3.6.2

Folding cycles

The idea of a folding bicycle appealed to Yvonne Rix but the volume

market was shrinking and tended to be dominated by cheap 20"

wheel imported machines. These sold at about £70 and had little

profit margin. As noted above, Raleigh produced a similar machine,

but this was dropped about 1989. In that year Raleigh started selling

the 26" wheel US-designed Montague Bi-frame, which was built

in Taiwan. It was sold as a Rudge, because the philosophy was, ‘If

it’s not made in Nottingham, it’s not a Raleigh’.

Yvonne Rix liked the Bi-frame which, as big-wheeled folders go is

a good machine. However, at about £350 when launched (= about

£500 today) it was relatively expensive. Furthermore, dealers

found it difficult to promote the important fact that it folded.

Rather too late, Montague evolved a display stand to emphasise this

feature. Despite strong efforts to promote the Bi-frame, sales were

poor and it was dropped early in the 1990s.

Thereafter Raleigh steered clear of folding cycles until the late

1990s. Then it marketed a derailleur-geared Rudge-branded 20"

wheel Dahon for about £300, including carry bag. Little was

done to promote this machine and at the time of writing it can be

bought as a clearance item at a considerable discount.

3.6.3

Hybrids

Yvonne Rix had anticipated that a replacement for the basic mountain

bike would be needed. She reasoned that customers would want to

progress from the relatively heavy but comfortable MTB to something

slimmer and lighter. But they would not go back to racing bikes,

with their relatively uncomfortable riding position, an uncomfortable

narrow saddle and narrow fragile wheels that got caught in potholes.

The MTB gave everything a racing bike did not: an upright riding

position, comfortable saddle, and wide tyres with a high degree

of puncture resistance. However, after riding it on the road for

a while, the downsides that became apparent were weight and rolling

resistance. Therefore, Rix proposed a machine that kept the good

braking, wide-ratio gears and other MTB advantages but with thinner

frame tubes and tyres that were a compromise between the knobbly

wide-section mountain bike tyre and the lightly treaded narrow-section

racing bike tyre. In effect, she devised an improved sports light

roadster with a more modern image.

Raleigh thus effectively invented the hybrid and therefore had difficulty

obtaining suitable tyres. Whereas today every Taiwanese tyre manufacturer

makes hybrid tyres, the only supplier in 1990 was Vredestein in

the Netherlands.

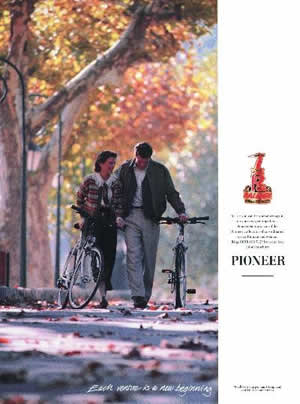

Launched in 1991, just as MTB sales dropped away, the Pioneer range

was promoted heavily and initially sold well. At the time of writing,

Pioneers are still made but the biggest marketing problem was the

lack of an easily remembered and well-understood generic name for

this type of machine. The UK industry used the term ‘hybrid’

which was unattractive to customers, giving a hint of ‘neither

fish nor fowl’. Competitors, reasonably enough, did not wish

to use the Raleigh name, Pioneer. The Germans called them trekking

bikes, which suggests to UK customers something rather arduous.

It is interesting to note that nine years after the Pioneer range

was launched, Trek were advertising hybrids as ‘a totally new

style of bike for a totally new style of biking’.

Pioneer: the birth of the hybrid.

............................................. .............................................

|